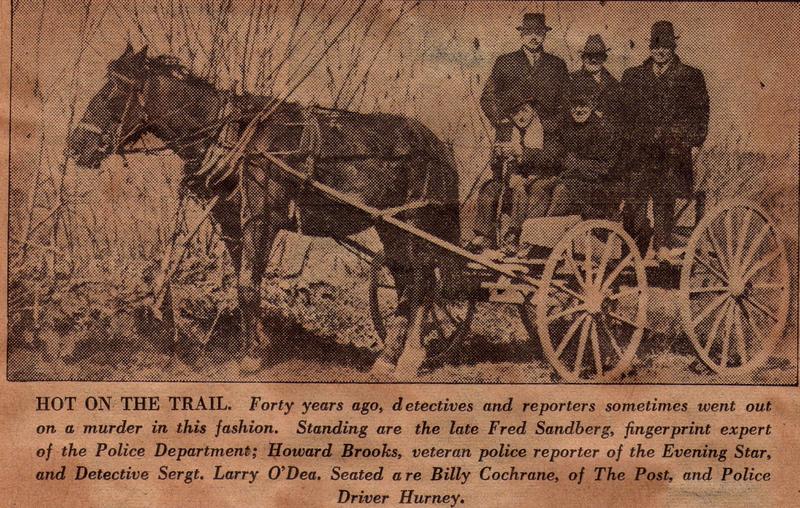

Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

1866 to 1899

1887 – The first in-custody death occurred when a women set fire to her clothes while in a cell at the 7th precinct and died of her injuries.

A man by the name of Charles Copeland went to Baltimore and, while intoxicated, claimed to be a D.C. Policeman and began making arrests before being arrested by Baltimore Police, (MPD)

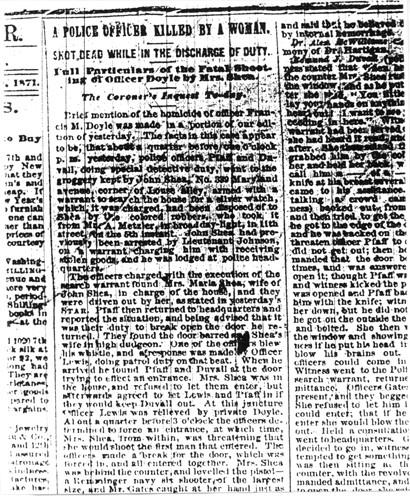

M.P.D.'s first Officer Killed in the Line of Duty

1881 – An eleven year old boy, Charles Taylor, was put on trial for the murder of Eddie Ford, (MPD).

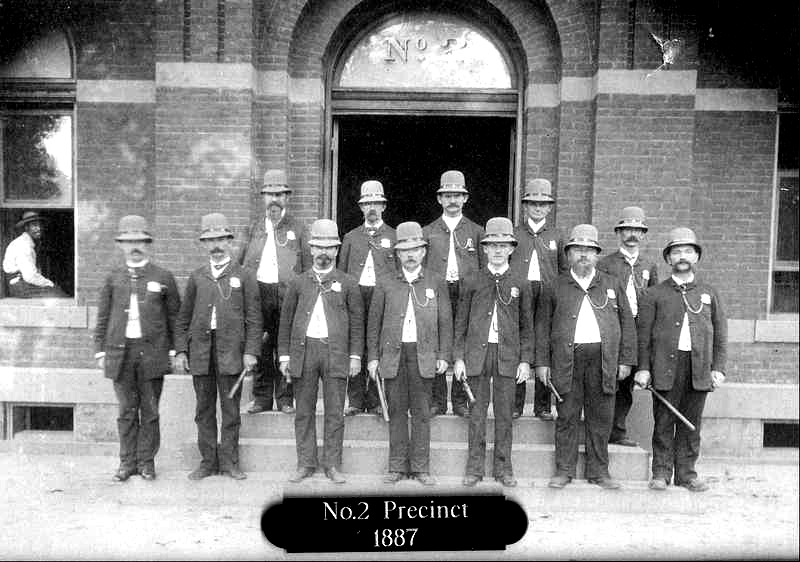

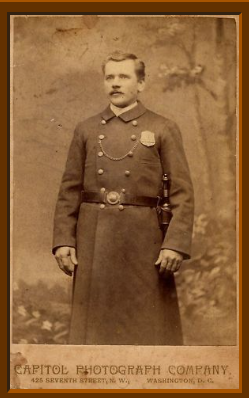

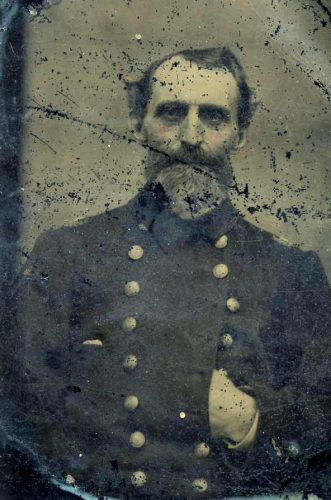

Photo provided by the M.P.D.

Photograph of 1890’s Metropolitan Police Officer.

1890 Washington D.C. Metropolitan Policeman

1889 – Major and Superintendent Moore re-issued an order prohibiting reckless and indiscriminate use of the police service revolver in the course of duty, (MPD).

1893 – The Metropolitan Police Department recorded 27,245 arrests, with a force of only about 400 officers, an average of 68 arrests per man, (MPD).

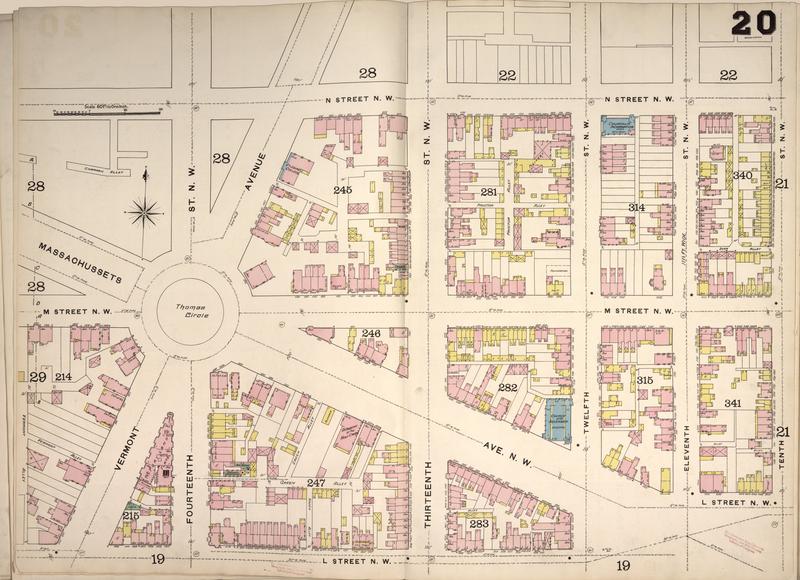

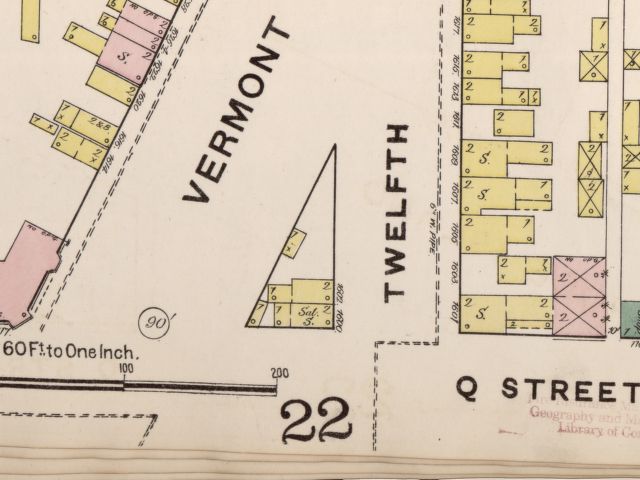

Map of Thomas Circle in 1888

The Sanborn fine insurance Map of the area around Thomas Circle in 1888. The yellow buildings are wooden frame structures and the pink are brick buildings.

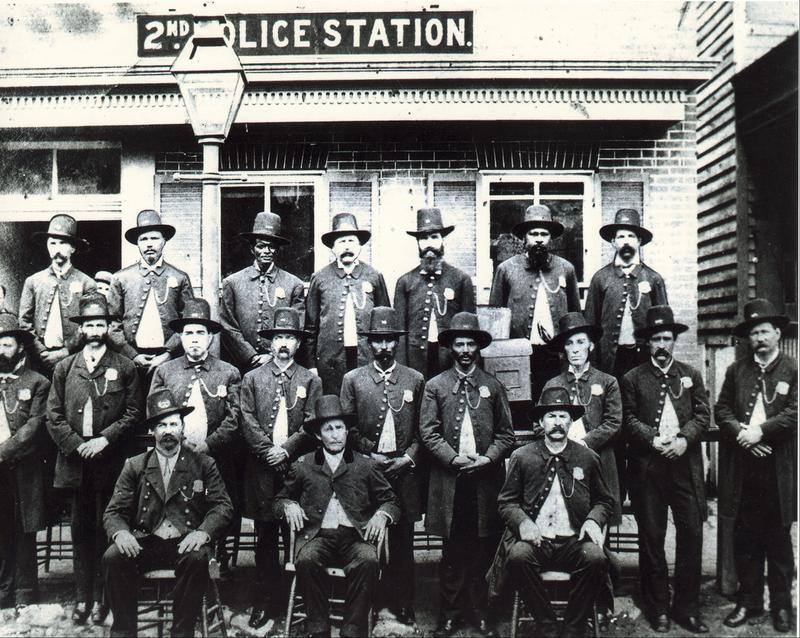

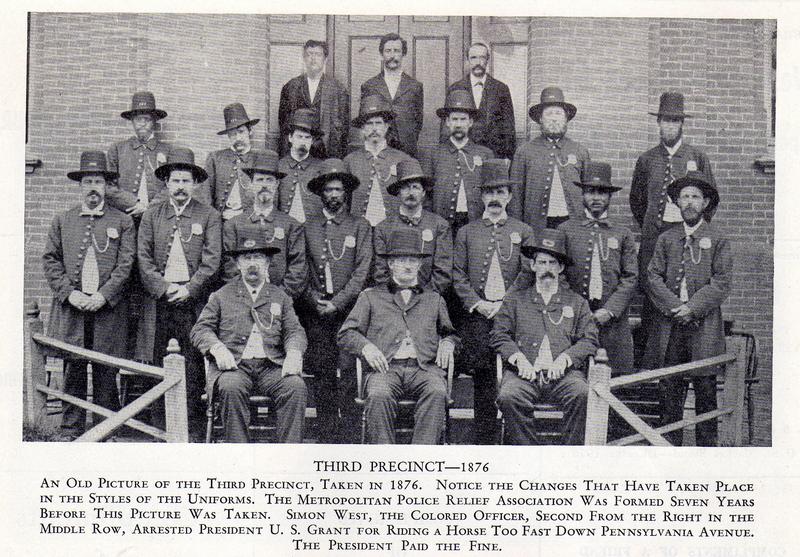

1878's Washington D.C. Metropolitan Police

This is the heading Lt. Hamilton K. Redway served with the M.P.D. in the area of 1865 to 1890. Lt Hamilton passed at the young age of 53.

I was contacted by the great-great grandson of Lt. Redway who was looking for information on the M.P.D. aside from this picture Kevin informed me of the following:

Hamilton K. Redway (1835-1888) served as a corporal in Company K, 24th Regiment of the New York Volunteers (1862-1863) and as lieutenant and later captain of Company F, 1st New York Volunteer Veterans Cavalry (1863-1865) during the Civil War.

After the war, Redway, who was a white man, was second lieutenant in Company D, U.S. Colored Cavalry (1866). By 1869 he was appointed to the Metropolitan Police Force of Washington, D.C and served in at least the 2nd and 4th Precincts, 1st Ward (possibly others).

He died of some sort of illness while still on the force on December 27th, 1888 – age 53

The killing of Officer Crippen

See this and other stories if you click on the above link to “D.C. Ghost Stories”

WASHINGTON, Nov. 6.–Three men are dead today in consequence of the affray in a part of the city called Hell’s Bottom, in the northern section of the city, referred to in The Sun this morning. Osborne Busey, a negro, was wounded by another negro, George Bush, who ran, but was pursued by Officer A. N. Crippen, who shot at him. The negro Bush took refuge in Bob Brown’s saloon, on Twelfth and Q streets northwest, and ran upstairs, saying he would kill any policeman who followed him. Officer Crippen was not daunted, but followed Bush upstairs where Bush fired at him, and Officer Crippen returned the fire until he fell dead, leaving Bush mortally wounded and speechless. The officer’s body was taken off in a patrol wagon and the wounded negroes carried to the hospital, where Busey died at 8 o’clock this morning and Bush was a corpse at 8 o’clock. Both had bad reputations. As all the parties to the tragedy are dead the coroner gave burial certificates without an inquest. No braver officer ever lived than officer Crippen. He came here from Dranesville, Va., in 1877. He had a wife, but no children.

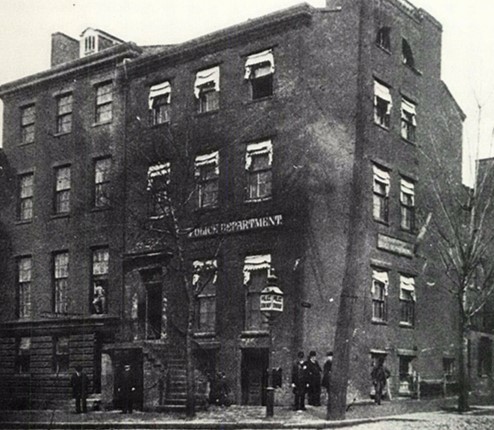

On Capitol Hill a few blocks from the Eastern Market Metro Station is a fully functioning relic of a time gone by, the Metropolitan Police Department’s First District Substation. MPD traces its origins back to the Civil War, when rapid government expansion, an incoming horde of unscrupulous opportunists and not a few drunken soldiers made the existing system of a fifteen-man auxiliary watch untenable.

Today, MPD is a thoroughly modern crime-fighting organization, but the 1D-1 Substation hearkens back to a different time—when patrolmen walked their beat, checking in via call boxes still visible on many city streets, and used whistles to call for backup. Local residents are largely familiar with it as the place to go to get parking permits for out-of-town residents, and a step inside gives a whiff of Joe Friday. It’s a throwback, a historic building still in active use, not gussied up with new wood paneling, with an actual desk officer, slightly bored and almost always helpful, there to answer questions.

Ghosts and cops have a long, symbiotic history together. In days past, and today to an extent, they would often be the only two classes of beings walking around deserted city streets at two o’clock in the morning. Many a ghost has been sighted by a police officer, and even when the ghost appears to someone else, reporters instantly turn to the officer on the local beat for confirmation. More often than not, the cop is a believer and can regale even cynical reporters with prior instances of apparitions, streets he won’t walk down and other dark doings of the night.

So it was no surprise a few years ago when a local MPD officer (who has asked to remain nameless) told a tale of a mysterious occurrence at the substation. It happened, as these tales so often do, on a dark and stormy night, when the officer was on desk duty at the front door. The station was equipped with a closed-circuit TV camera, naturally, and just when the officer felt that he was losing the long war against drowsiness, he noticed another officer on the TV, which was odd, as he was mortally certain that he was alone in the building.

It was hard to see, but the phantom officer didn’t look like any of the police officers then assigned at the station. What’s more, he was wearing an anachronistic jacket and a long coat, seemingly dripping with rain. Via camera, our confused and slightly apprehensive officer tracked the mysterious being as he headed out a side entrance and disappeared into the gloom. A search was made: the side door was still locked and showed no sign of being opened recently, and there were no wet floors that you might expect from a dripping coat. Playing back the tape revealed only the ordinary quiet of a virtually empty police station in the wee hours of the morning.

The officer had no explanation of the tale and has often managed to convince himself that it was all in his head. But the question lingers: who was the phantom officer?

Well, there’s certainly a candidate that fits the bill. On the evening of March 5, 1909, at 7:45 p.m., policeman John W. Collier boldly walked into what was then the Fifth Precinct station house and shot the precinct commander, Captain William H. Mathews, five times, emptying the last three rounds directly into his head. Captain Mathews’s deputy, Lieutenant J.L. Sprinkle (longtime favorite of Ghosts of DC readers!), and two other officers instantly wrestled Collier to the ground, but the damage was done. A doctor was summoned, but he could only confirm what the officers already knew: Captain Mathews had been ruthlessly killed without warning by one of his own officers.

Collier offered no resistance nor defense. “I shot him, all right, and I’ll give my reasons later. I was rational and sober, and there was nothing wrong with me,” he calmly told Lieutenant Sprinkle as he was taken to the District Jail.

In the coming days, some semblance of a picture gradually emerged of the events of the fifth and before. Captain Mathews was known as a by-the-book cop, a “strict disciplinarian,” as the Washington Times put it, but he was later accused by defense attorneys of being “quarrelsome, vindictive, and violent.” Collier was a slacker who had been before the trial board (a disciplinary board for police officers) nine or ten times. His mother defended her son but offered what was perhaps not the best defense: he felt he was being persecuted for being late.

On the day of the murder, Collier was supposed to go on duty at midnight. A 4:00 p.m., he called in sick. The captain had had enough and told him to come in to the station so that he could see if Collier was sick or not. Just past 7:00 p.m., Mathews received another phone call from Collier that made him turn red and slam “the receiver on the hook with such vigor that the telephone nearly overturned.” Collier showed up about half an hour later, talked to no one and walked by the other officers, who nudged one another and whispered, “He’ll get his when the captain sees him.” Seconds later, the shots rang out.

Collier testified several months later that this was a case of self-defense. He said that the captain had told him in the telephone exchange, “I wouldn’t give 15 cents for your chances when you come into the office.” Upon his arrival, the captain told him that his goose was cooked, to which Collier replied, “I think you have another thing coming, Captain.” Then, according to Collier, Captain Mathews muttered, “Damn you, I’ll get you for that,” and reached toward his hip pocket. Thinking that Mathews was going to shoot first, Collier fired and killed him.

The trial was a particularly tense affair, as at one point the defense attorney took a swing at the district attorney. The assistant district attorney jumped between them and got a punch in the face for his efforts. The fight was then broken up by a police officer and, believe or not, the defendant. Perhaps that swung the jury a bit, or perhaps they found his story plausible, as Collier was found guilty of only manslaughter and was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Is Captain Mathews the mysterious ghost seen on the video cameras? Who knows, but to answer the inevitable question, it was cold and clear out on the night he was murdered, although Washington was recovering from a snowstorm so intense the night before that it drove President Taft’s inauguration indoors. So perhaps it was melting snow on the overcoat?

Cabinet photograph of a DC Metropolitan Police Officer

Cabinet photo of a 1880’s Sgt. with the Washington D.C Metropolitan Police Department

October 11, 1890

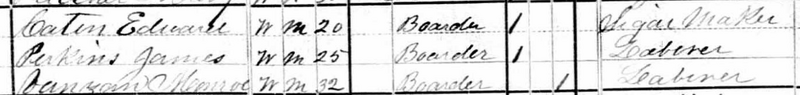

Washington, Oct. 10.–One of the most remarkable suicide ever known in this city occurred tonight. A young man whose name is thought to be Edward Caton, killed himself by forcing his neck between the iron palings of the fence that surrounds the grounds at the back of the White House. Exactly what time the suicide occurred is not known, for after the gates of the White House grounds are closed, but few people pass around the circular walk that skirts them, just outside the iron fence. The fence itself is about five feet high, with the iron palings, about two and a half inches apart, projected six inches above the iron rail that holds them in place. There are both gas and electric lights about the place, but owing to the branches of the heavy trees which overhang the walk from the grounds of the Executive Mansion it is dimly lighted, and from any distance objects can scarcely be distinguished. Directly south of the White house and at one of the darkest points on the walk the suicide occurred.

A young mulatto woman, who was hastening through the grounds on her way homeward from some place of employment down town, discovered the body about 7.30 o’clock. The darkness prevented her from seeing that the man was dead, but the attitude and, as she supposed, the intent with which he was peering through the fence at the Executive Mansion caused her to think that some thing was wrong, and she retraced her stp and informed a park watchman of what she had seen. The watchman hastened to where he stood and was about to accost him, when he discovered that the man’s neck was jammed between the iron palings of the fence until the front portion rested upon the iron rail.

The watchman at once summoned police man Heller to his assistance, and together they extricated the man from his position. This was not done, however, without considerable difficulty, for so closely did the palings grip the neck of the suicide that it required a strong effort on the part of both the officers to release him.

The body was still warm, and as soon as a patrol wagon was summoned it was placed in it and the horse driven at a furious gallop to the Emergency Hospital, where it was hoped that consciousness might be restored, but medical assistance came too late, and all the physicians could do was to determine that life was extinct.

In the pockets of the deceased were found cards bearing the name of Edw. Caton, and showing that Caton had been a member of the Knights of Labor and also of the Printers’ Union, but whether or not Caton and the dead man were identical the police were unable to determine. In consequence nothing is known either of the man’s circumstances or the causes that led him to take his own life except the cards referred to. Neither documents nor money were found in the dead man’s pockets.

It was thought for a time by police that possibly the man had been foully dealt with and his neck jammed between the palings in order to give his death the appearance of suicide. A careful examination of the place where the body was found was therefore made, but no signs of a scuffle having taken place or of blood spilled could be discovered, nor did the body show marks of violence except at the neck where the iron fence had gripped it, while the neat suit of black clothes in which it was dressed were not in any way disarranged.

Late tonight it was ascertained that Caton was a cigarmaker, employed in West Washington.

– Baltimore Sun

1880 U.S. Census, Edward Canton, listed as a 20 year-old cigar maker living as a boarding tenet on Bridge Street, (now M Street, NW in Georgetown.)

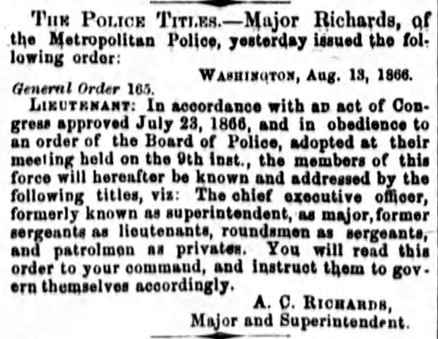

Police Rank changes in 1866.

Photograph of 1890’s D.C. Metropolitan Police Officer.

Three irate women with horse whips and a yelling special policeman gave plenty of amusement last Friday to a number of people who stood outside of a grocery store on Twenty-sixth, between F and G streets north west [sic], George Cunningham is the name of the special officer, and he is employed by the storekeepers around “Foggy Bottom” to watch their places of business.

He was supposed to have been the author of some derogatory reports against the character of Harriet Payne, a white woman who lives on Water street, in Georgetown. The report reached the ears of the woman, and she traced it to the special officer. The woman took into her confidence her two sisters and started out for revenge.

They secured three heavy horsewhips, and on Friday night by strategy got the watchman to enter the grocery store. Once inside the front door was locked and the key taken away. Seeing the determined look on the faces of the females the special suspicioned that something was wrong and attempted to escape. This was the signal for the women, and all three started in to lash the man. Over his head and across his back the blows rained down on the unfortunate watchman. There was no escape from the blows, and not until the women were exhausted did they cease from their labors. The door was then opened and the watchman allowed to go, and he immediately vanished, leaving behind his hat.